|

Go to Indian-Tales home |

; |

|

|

Go to Indian-Tales home |

; |

|

|

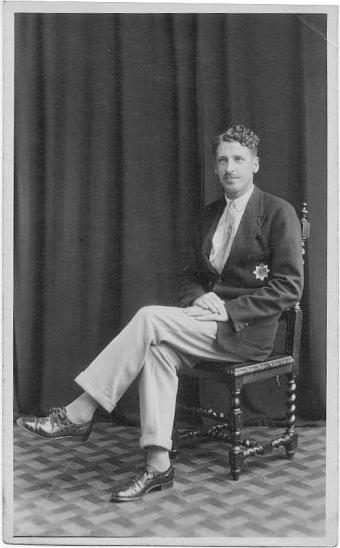

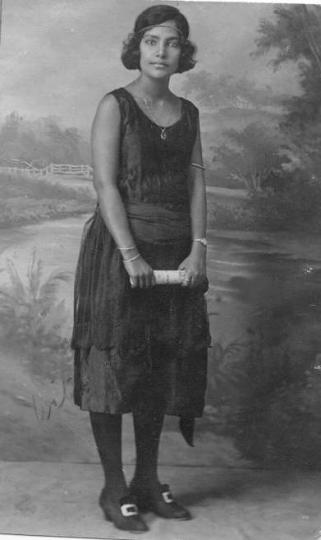

Indian Tales Patrick O'Meara Author’s Note. This collection of stories and memories is not intended to be an exhaustive account of our family’s childhood years in India, Ireland and England. Sometimes, it has seemed relevant to introduce comments and other post-colonial tales in order to paint a clearer picture of the times. For these occasional detours, I would crave the indulgence of my readers. It is intended to remind our branch of the O’Meara family, my beloved wife and, in particular, my own two sons Karl and Kieron — who “have heard it all before” —, of many hours passed in the telling of them. It is also intended as an easy summary of the kind of living we enjoyed and sometimes suffered in those faraway days. It is a summary intended, not only for our children, but also for their children and grandchildren. We had no television, computers, personal stereos, refrigerators or other labour-saving kitchen equipment. Neither did we have “designer” clothing or the other “must have” accoutrements of today’s living. Yet I cannot ever remember a single day when I was “bored” as so many youngsters claim to be today. My advice to all who read this collection of memories is to value each day of their own lives as precious and exciting building blocks of their own stories — even though they may sometimes include sorrowful or tragic moments — that they too might one day tell their own families. O’M — 1999 In Memory Dad - Edwin Bernard O’Meara 1903-1971 and Mum - Elise (ne) De Rozario 1900-1995 DedicationTo My sons, Karl and Kieron who suggested it. to My wife, Pirkko, who compelled its writing and to My brothers and sisters and their families  Dad – circa 1922

Mum – circa 1922 |

| I |

was on my way to school, alone, reluctant and as usual, looking

for any excuse to play truant…

The man looked at me and, putting his hands together as if in prayer, he greeted me.

“Salaam, Baba Sahib.”

“Are you a khansama [2] ?”, I asked.

“Yes, Baba Sahib, I am a khansama.”

“Well, my mother needs a khansama, so you’d better come home with me.”

We were without a cook and I knew that Mum needed one. I took Zahir back to the house. Mum interviewed him and he got the job.

Zahir soon proved to be an excellent cook and Mum was absolutely delighted.

“But how did you find him?”, she asked me later.

“I knew you needed a cook, mummy, so I just asked him.”

“But how did you know he was a cook and that he needed a job?”, she insisted.

“I didn’t know he was a cook or if he needed a job. He was standing in the road so I just went up to him asked him.”

That was the relaxed, easy way of India in the days of the British Raj. I was five years old.

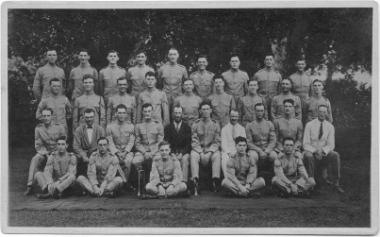

Buglers – Dad seated second from right – circa 1919

Bakers – Dad seated second from left — circa 1929

My father, who had enlisted as a bugle boy in the army in Portsmouth in 1919 at the age of fifteen, was now aged twenty-six and a Master Baker in the Royal Indian Army Service Corps (RIASC). He had transferred from the Royal Horse Artillery to the Indian Army within three years or so of arriving in the India and was stationed in Mt Abu to develop and open a military bakery.

Transferring from the British Army to the Indian Army was not an unusual practice for British-born troops because promotion prospects were a lot better and, of more consequence still, the transferee immediately qualified for expatriate and overseas allowances. In addition, his leave allowance was quite substantially increased and he could thus, in addition to annual “local leave” of about four to six weeks, look forward to a year’s “home-leave” every few years. “Not to be sneezed at.” Dad often said.

We lived in a nice bungalow built on top of a giant rock overlooking the Gymkhana Club and its playing field. The rock, which had a surface area of about four acres and a height of about seventy feet at its highest point above the surrounding terrain, was a convenient foundation for the bungalow. Many other buildings, of sizes varying from single-roomed hut-dwellings to large palaces, used the same opportunely available foundations of other rock masses. It was really only a matter of a simple leveling of the surfaces for a secondary foundation and then constructing the appropriate building.

Mt. Abu used to be the only town atop the Aravali Range of mountains in those days. But over the years since 1947 surrounding villages have grown quite considerably and are now regarded as towns in their own right.

We used to refer to the Aravali Range as “hills” — in fact Mt Abu was a well-known “hill station”, a place to which Europeans could repair during the high temperatures of the hot season on the plains — but the highest peak is over 6000 feet above sea level and so it is not really incorrect to speak of them as “mountains” in the European sense of the word.

[1] The British Empire with particular reference to India.

[2] A cook.